- Home

- James Tully

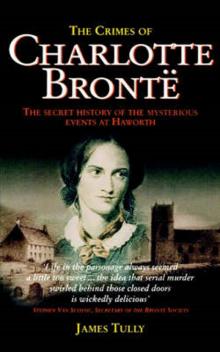

The Crimes of Charlotte Bronte

The Crimes of Charlotte Bronte Read online

THE CRIMES OF

CHARLOTTE BRONTË

THE CRIMES OF

CHARLOTTE BRONTË

The secret history of the mysterious events at Haworth

James Tully

Robinson

LONDON

Para mi querida J . . . – whom I met when she was but seventeen and have loved deeply for some fifty years

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson Publishing Ltd 1999

This paperback edition 1999

Copyright © James Tully 1999

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN 1-84119-131-0

eISBN: 978-1-47211-199-9

Printed and bound in the EC

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

Cover copyright © Constable & Robinson

Introduction

My name is Charles Coutts, and I am a partner in the firm of solicitors Coutts, Heppelthwaite and Larkin, which was established in 1788 by my great-great-great-great-grandfather, Henry Coutts.

Henry began his practice from one room which he rented in a large four-storied building in Keighley, Yorkshire. He prospered, and, over the centuries, more and more rooms were acquired until, in 1926, my grandfather bought the freehold of the entire property. Then, three years ago, we received an offer for it which we could not refuse.

Some developers were willing to pay a considerable sum in order that they might demolish the building and then use the entire, very large, site for the construction of a shopping mall. Actually we were, in effect, made two offers. We could either have the total amount in cash, or have our pick, at a favourable price, of a spacious suite of offices in a new block which was nearing completion, and receive the balance.

I discussed the matter with the other partners at some length, and in the end we realized that we should be foolish not to jump at the proposal. Our premises needed a lot spending on them, and they were already costing the earth to heat and maintain. It was a heaven-sent opportunity to cut our losses and move, and that was just what we did – after opting for the ‘part-exchange’ deal.

As we had anticipated, the changeover was a major upheaval. To move one’s home is bad enough, but to clear such a large building of all the junk which had accumulated in over two centuries was a nightmare. It had been decided that it would be best if we dealt with the removal floor by floor, and transferred to our new offices gradually. We began, therefore, with the two large attics.

Many years had slipped away since I was last up there – as a small boy during the Second World War – and, remembering what it was like then, it was with some trepidation that I ascended the rickety stairs to make an inspection.

What I beheld, when I finally managed to force open the first door, confirmed my memories – and my worst fears. The rooms were packed from floorboards to rafters. It seemed that my forebears had been unable to throw away anything whatsoever, and it was going to be a task of gargantuan proportions to sort through what was there.

I undertook the supervision of the work myself, mainly because I did not wish anything of value to be discarded, but also because I was interested in my ancestry and the history of the firm. In other words, as I overheard one of my partners say, I was ‘both acquisitive and inquisitive’!

It was a slow business but, with the help of four stalwart workmen, I was able to make steady and rewarding progress. A couple of containers of rubbish went off to the tip, but there were many other items, some genuine antiques, which we sold at prices which astounded us.

There was, however, one piece of furniture which I earmarked for myself. It was a handsome George IV bureau/bookcase, which I thought would stand nicely in my study. I gave it a rough wipe with a rag, made sure that it was free from woodworm, and then had it taken to my home where it was stored, temporarily, in the garage.

What with the move, and other matters, it was some weeks before I was able to get round to a closer inspection. Eventually, however, a weekend arrived when I had the time to give it a good cleaning in order to see whether any restoration would be necessary.

I lowered the flap which formed the writing-top, and then removed all the drawers before starting work. It appeared to be in good condition, and I was feeling quite pleased with myself as I beavered away with cloth and polish. Then, suddenly, as I was rubbing the side of the large central section, there was a loud ‘click’ and, to my utter amazement, the bottom of the section swung up.

What was revealed was one of those secret compartments so beloved by nineteenth-century craftsmen. The base of the middle section was false, and obviously I had touched something which released what was, in fact, a carefully hinged lid to the hiding-place below.

Among other bits and pieces, it contained various documents which, I was to discover, had been placed there by my great-great-grandfather who died, suddenly and quite unexpectedly, in 1878. All had been of a highly confidential nature at the time, but most were now no longer so and need not concern us here. However, the contents of a brown paper parcel have intrigued me ever since I read them, and have given me many a sleepless night.

The parcel measured some twelve inches by ten, and was about three inches thick. It was sealed with red wax, imprinted upon which was the name of our firm, and tied neatly with white tape, the knot of which was also sealed and bore the signet of my ancestor James Coutts. On the front of the parcel, in his magnificent copperplate handwriting, were the words: ‘Statement sworn to by Miss Martha Brown of Bell Cottage, Stubbing Lane, Haworth, on January 8th, 1878. Not to be opened until after her death, and that of Arthur Bell Nicholls, Esquire, of Hill House, Banagher, King’s County, Ireland.’

It was the stuff of which murder mysteries are made and, never having seen similar phraseology before in my professional career, my curiosity knew no bounds. I was filled with anticipation as – oh, so carefully – I slit open the parcel and examined the contents.

They consisted of a pile of rather tattered old school exercise books, one of which, I found later, had been used as something of a diary by Anne Brontë.

At the end of the final paragraph, on the last page of the books, there was a deposition that what had been written in the books was true. That was followed by a form of wording which authorized James Coutts or his successors to use the information contained in the books in any way they saw fit, but only after the deaths of the signatory and Mr Nicholls. Below that, and witnessed by James Coutts and one of his clerks, was the signature ‘Martha Brown’, written in a good hand for one who, I was to discover, had been a mere servant woman.

I had to read the books several times before I had a proper appreciation of the enormities which they detailed. Apparently Martha Brown had been a servant in the employ of the legendary Brontë family of Haworth – which is some five miles from Keighley as the crow flies. Among other things, she claimed that most of the Brontë family had been murdered, and that she was privy to one of the killings. What she alleged she had witnessed made startling reading, especially as part of it was self-incriminatory, but, if it was all true, I understood why she had seen fit to have her testimony signed and sealed.

Was it true,

though? Or could it be true? Although their former home was so close to mine, I must confess that I knew very little about the Brontës. I had once accompanied my wife, under sufferance, to Haworth and the Parsonage – but had thought the best part of the trip was our visit to the Black Bull afterwards! From holidays in Cornwall, I also knew the house in Penzance in which Mrs Brontë had lived until she married. That, however, was the sum total of my knowledge of the family. As for the literary works of the three daughters, I had heard of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights but had never read them.

What Martha Brown deposed was to alter all that. Clearly I needed to check on all the available evidence. I wanted to know why she had chosen James Coutts’ firm, and whether what she had told him was in keeping with the known facts about the Brontës.

The answer to my first query was easily discovered. I found that our firm had acted for the Haworth Church Trustees on many occasions, a fact of which Martha might have been aware both from working at the Parsonage and being the daughter of the sexton at Haworth. It was logical, therefore, that she should have come to us, and the senior partner would have been the only person to whom she would have imparted such extraordinary information.

As for my other question, I began on the premise that James Coutts must have thought that there was at least some truth in what she had confided. Otherwise, from what I had read of him, he would probably have sent her packing with a stern warning ringing in her ears. I then embarked upon what was to become a lengthy process of research, but it did not take all that long to come to the conclusion that there was something seriously amiss with the generally accepted legend of the Brontë family.

It all seemed far too good to be true. Three almost saint-like sisters – Charlotte, Emily and Anne – live with their stern, but equally saint-like, father in a grim parsonage in a wild part of England. After very little formal schooling, and not until they are all far into their twenties, each writes – in the very same year – a romantic novel which sells well. Within ten years they are all dead, but they live on in their books – which continue to sell well nearly 150 years after the last sister’s death.

Interwoven with their lives is a young and handsome curate who arrives, very coincidentally, at the start of the year in which the novels are written. He eventually marries the eldest sister who dies, tragically, whilst carrying their first child. Husband, heartbroken at the loss of his one true love, vows that he will care for her aged father for the rest of his life. This he does, for six long years, until the venerable, white-haired patriarch finally departs to meet his Maker.

The sad and lonely widower then rides off into the sunset to try to find some meaning in Life. Curtain down; not a dry eye in the house.

Of course, being Victorian, the story has to paint a moral, and this is provided appropriately by the sisters’ brother, Branwell Brontë. He is intelligent, artistically gifted, and shows great promise. However, he falls in with bad companions and is easily led into a life of debauchery. Inevitably he comes to a sad, but only to be expected, end through his addiction to drink, drugs and gambling. Let that be a lesson to us all, and an encouragement to sign the Pledge before it is too late!

I fear that, according to Martha Brown, the reality was very different. The Brontës were all fallible, and subject to short-comings as are we all.

Having checked her story, and what Anne Brontë had written, against the known facts, I was in a dilemma. I had been able to discover nothing which contradicted what she had to say. Initially I had made my enquiries merely to satisfy my own curiosity; but now that I had done so, and become convinced of the veracity of the documents, what should my next step be?

Probably the easiest thing would have been to have destroyed the books, or at least kept the whole matter to myself. Nobody would have been any the wiser, and the ‘authorized version’ of the Brontë legend would have continued to be accepted. On balance, however, and only after a great deal of thought, I decided that the statement and the ‘diary’ were historical documents which should be made public.

Here, then, is what Martha recounted all those years ago. As it incorporates all the facts that Anne recorded, I have seen no reason to quote verbatim from her book. I have other plans for that highly valuable document.

In order to make Martha’s deposition understandable, and to provide readers with background and other information, I have replaced the more obscure of the old Yorkshire dialect words, inserted some punctuation and added, at the end of each chapter, comments on the results of my research – to distinguish them from Martha’s text the reader will find my initials [] at the start of each of these sections. The Biblical quotations at the start of each chapter are my idea, and were introduced in order to break up Martha’s continuous narrative and because they seemed appropriate. Essentially, however, the tale belongs to her.

I am very conscious of the possibility that the publication of this account may cause offence in some quarters. That, I am sure, was not Martha’s intention, and it is certainly not mine. I shall therefore be sorry if such proves to be the case. It is merely that, as her statement fits all the known facts, I feel I have an obligation, especially to the Brontës, to let it be known.

So come along with Martha and me, step by step, and see what you think. If, as I did sometimes, you find anything which is difficult to accept, compare it with the popular version and then with the facts and see which you consider the more reasonable.

Obviously each reader will come to her or his own conclusion, and there will probably be many who, initially, will doubt Martha’s tale – as indeed I did. However, after asking myself what she had to gain by inventing such a story, I approached it with an open mind and all I ask is that you do the same.

If, in the end, she has achieved nothing more than to cause you to doubt the traditional Brontë story I am sure that Martha Brown’s spirit, and those of the Brontës too come to that, will rest more easily.

Chapter One

‘Lo, mine eye hath seen all this, mine ear hath heard and understood it.’

Job 13:1

My name is Martha Brown, and for over 20 years I was servant to the Brontë family at Haworth Parsonage. During my time there I witnessed and overheard many things that have stayed unknown to the world outside, and I was told of other matters by my Father and the Reverend Arthur Bell Nicholls, who was Mr Brontë’s curate for about 16 years. Even so, there were happenings that were not fully clear to me at the time, but so much has come out since the Brontës died that I can now see the whole picture.

For a long while now what I know has been a burden to me and, as I have not been too well of late, I now feel that it is high time that I set my mind at rest. I shall ask that what I write is not read until after my death, and even then it should not be made public if Mr Arthur Bell Nicholls, now of Hill House, Banagher, King’s County, Ireland is still alive. Although he has much to answer for, he has never rendered me any harm and I do not wish any ill to befall him through me.

What I have to say begins in 1840, when I was only just over 12 years of age. My Father, John Brown, was a stone mason in Haworth. He was also the Sexton of the Church there and Master of the Freemason Lodge. We lived in a cottage called ‘Sexton House’ in The Ginnel – near the Church and right next door to the National School, where I also went to Sunday School. Father used a barn across The Ginnel from the Parsonage for his work.

I was very happy with my Mother and Father and sisters until shortly after my 12th birthday, when Father told me that as I was the oldest I would have to earn my keep. He said he had had a word with Mr Brontë and I was to work at the Parsonage and live there. Life was never the same for me after that.

There were many tales about the Parsonage, and I was very ill at ease on the morning that I had to start my job, so Father took me by the hand and we walked there together, carrying the bits and pieces that I was taking with me.

First of all we met the Parson, Mr Brontë, and his dead wife’s sister, Miss Branwe

ll, who had come up from Cornwall to look after the family when Mrs Brontë died nearly 20 years before the time that I am talking about. Mr Brontë was only 63 then, with Miss Branwell being but a few years older, but they both seemed very old to me, and I was a little afraid of them. Mr Brontë spoke to me kindly enough though, as did Miss Branwell after him and Father had left the room. She showed me the kitchen and the other rooms downstairs, and then took me to meet Mrs Tabitha Aykroyd.

In truth, Miss Aykroyd – as we called her – knew me very well, as I did her. She was a village widow-woman who was nigh on 70 then, and who had worked at the Parsonage for 15 years. The Brontë children looked upon her as an aunt, and called her ‘Tabby’, but talk in the village had it that, at one time, she had had a very different friendship with Mr Brontë. Now, though, the years were catching up with her, and also she had had a fall and broken her leg which was not mending as it should, so Father and Mr Brontë had agreed that I should be taken on to help out.

The work at the Parsonage was hard, and the house dreary and damp with no curtains at the windows because Mr Brontë was afraid of a fire. I had to get up very early, and I slaved for many hours, doing all manner of rough jobs, some of which I hated, from scrubbing the flags with sandstone, which often left my hands bleeding, to making ready the vegetables, and all for only 2/3d a week which I had to give to Mother with naught for myself but what she chose to give me from time to time. As I got older I was to be relieved of many of the worst jobs by younger girls, and I would be allowed to work upstairs, becoming something of a maid to the sisters. However, I did not know that then and I was very unhappy.

Night after night I was kept working to all hours. I would trail upstairs so tired out, and many a time in tears. I had to share a bedroom with Miss Aykroyd, and that had not bothered me when first I was told about it for I was used to sharing with my sisters in our crowded house. When it came to it though, I did not like it one jot. Miss Aykroyd snored a great deal, and often moaned, I suppose from the pain in her leg. But it was not only that – she got up two or three times in the night to pass water and made such a noise that some nights I had barely any sleep and would start work tired out already.

The Crimes of Charlotte Bronte

The Crimes of Charlotte Bronte